![[Previous]](prev.gif) |

![[Contents]](contents.gif) |

![[Index]](keyword_index.gif) |

![[Next]](next.gif) |

![[Previous]](prev.gif) |

![[Contents]](contents.gif) |

![[Index]](keyword_index.gif) |

![[Next]](next.gif) |

This chapter includes:

|

This chapter concentrates on working with files in the QNX 4 filesystem, which is the default under Neutrino and is compatible with the older QNX 4 OS. For more information, see the Working with Filesystems chapter in this guide. |

In a Neutrino system, almost everything is a file; devices, data, and even services are all typically represented as files. This lets you work with local and remote resources easily from the command line, or through any program that works with files.

Neutrino supports the following types of files, and ls -l uses the character shown in parentheses to identify the type:

A directory is implemented as a disk file that stores a list of the names of files and other directories. Each filename is associated with an inode (information node) that defines the file's existence. For more information, see "QNX 4 filesystem" in Working with Filesystems.

Some files are persistent across system reboots, such as most files in a disk filesystem. Other files may exist only as long as the program responsible for them is running. Examples of these include shared memory objects, objects in the /proc filesystem, and temporary files on disk that are still being accessed even though the links to the files (their filenames) have been removed.

To access any file or directory, you must specify a pathname, a symbolic name that tells a program where to find a file within the directory hierarchy based at root (/).

A typical Neutrino pathname looks like this:

/home/fred/.profile

In this example, .profile is found in the fred directory, which in turn resides in the home directory, which is found in /, the root directory:

Like Linux and other UNIX-like operating systems, Neutrino pathname components are separated by a forward slash (/). This is unlike Microsoft operating systems, which use a backslash (\).

|

To explore the files and directories on your system, use the ls utility. This is the equivalent of dir in MS-DOS. For more information, see "Basic commands" in Using the Command Line, or ls in the Utilities Reference. |

There are two types of pathname:

For example, if your current directory is /home/fred, a relative path of .ph/helpviewer is the same as an absolute path of /home/fred/.ph/helpviewer.

The pathname, /home/fred/.ph/helpviewer, actually specifies a directory, not a regular file. You can't tell by looking at a pathname whether the path points to a regular file, a directory, a symbolic link, or some other file type. To determine the type of a file, use file or ls -ld.

The one exception to this is a pathname that ends with /, which always indicates a directory. If you use the -F option to ls, the utility displays a slash at the end of a directory name.

Every directory in a QNX 4 filesystem contains these special links:

So, for example, you could list the contents of the directory above your current working directory by typing:

ls ..

If your current directory is /home/fred/.ph/helpviewer, you could list the contents of the root directory by typing:

ls ../../../..

but the absolute path (/) is much shorter, and you don't have to figure out how many "dot dots" you need.

|

Flash filesystems don't support . and .. entries, but the shell might resolve them before passing the path to the filesystem. You can also set up hard links with these names on a flash filesystem. |

In some traditional UNIX systems, the cd (change directory) command modifies the pathname given to it if that pathname contains symbolic links. As a result, the pathname of the new current working directory -- which you can display with pwd -- may differ from the one given to cd.

In Neutrino, however, cd doesn't modify the pathname -- aside from collapsing .. references. For example:

cd /home/dan/test/../doc

would result in a current working directory of /home/dan/doc, even if some of the elements in the pathname were symbolic links.

Unlike Microsoft Windows, which represents drives as letters that precede pathnames (e.g. C:\), Neutrino represents disk drives as regular directories within the pathname space. Directories that access another filesystem, such as one on a second hard disk partition, are called mountpoints.

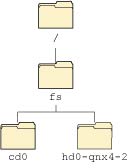

Usually the primary disk-based filesystem is mounted at / (the root of the pathname space). A full Neutrino installation (such as a self-hosted QNX Momentics development installation) mounts all additional disk filesystems automatically under the /fs directory. For example:

So, while in a DOS-based system a second partition on your hard drive might be accessed as D:\, in a Neutrino system you might access the second QNX 4 filesystem partition on the first hard drive as /fs/hd0-qnx4-2.

For more information on where to find things in a typical Neutrino pathname space, see "Where everything is stored," later in this chapter. To learn more about mounting filesystems, see Working with Filesystems and Controlling How Neutrino Starts.

When you list the contents of a directory, the ls utility usually hides files and directories whose names begin with a period. Programs precede configuration files and directories with a period to hide them from view. The files (not surprisingly) are called hidden files.

Other than the special treatment by ls and some other programs (such as the Photon file manager, pfm), nothing else is special about hidden files. Use ls -a to list all files, including any hidden ones.

Filename extensions (.something at the end of a filename) tell programs and users what type of data a file contains. In the QNX 4 filesystem (the Neutrino native hard disk filesystem), extensions are just an ordinary part of the filename and can be any length, as long as the total filename size stays within the 505 byte filename length limit.

Most of the time, file extensions are simply naming conventions, but some utilities base their behavior on the extension. See "Filename extensions" later in this chapter for a list of some of the common extensions used in a Neutrino system.

You may have noticed that we've talked about files and directories "appearing in" their parent directories, rather than just saying that the parent directories contain these files. This is because in Neutrino, the pathname space is virtual, dictated not just by the filesystem that resides on media mounted at root, but rather by the paths and pathname aliases registered by the process manager.

For example, let's take a small portion of the pathname space:

In a typical disk-based Neutrino system, the directory / maps to the root of a filesystem on a physical hard drive partition. This filesystem on disk doesn't actually contain a /dev directory, which exists virtually, adopted via the process manager. In turn, the filename ser1 doesn't exist on a disk filesystem either; it has been adopted by the serial port driver.

This capability allows virtual directory unions to be created. This happens when multiple resource managers adopt files that lie in a common directory within the pathname space.

|

In the interests of creating a maintainable system, we suggest that you create directory unions as rarely as possible. |

For more information on pathname-space management, see "Pathname Management" in the Process Manager chapter of the System Architecture guide.

Neutrino supports a variety of filesystems, each of which has different capabilities and rules for valid filenames. For information about filesystem capabilities, see Working with Filesystems; for filesystem limits, see Understanding System Limits.

The QNX 4 filesystem is the normal hard-disk filesystem that Neutrino uses. In this filesystem, filenames can be up to 48 bytes long, but you can extend them to 505 bytes (see "Filenames" in Working with Filesystems). Individual bytes within the filename may have any value except the following (all values are in hexadecimal):

If you're using UTF-8 representations of Unicode characters to represent international characters, the limit on the filename length will be lower, depending on your use of characters in the extended range. For more information on UTF-8 and Unicode, see the Unicode Multilingual Support appendix in the Photon Programmer's Guide.

You can use international characters in filenames by using the UTF-8 encoding of Unicode characters. If you're using the Photon microGUI, this is done transparently (you can enter the necessary characters directly from your keyboard, and the display shows them correctly within the Photon file manager). Filenames containing UTF-8 characters are generally illegible when viewed from the command line.

You can also use the ISO-Latin1 supplemental and PC character sets for international characters; however, the appearance of these 8-bit characters depends on the display settings of your terminal, and might not appear as you expect from within Photon or in other operating systems that access the files via a network.

Most other operating systems, including Microsoft Windows, support UTF-8/Unicode characters, and their filenames appear correctly in the Photon microGUI environment. Filenames from older versions of Microsoft Windows may be encoded using 8-bit characters with various language codepage in effect. The DOS filesystem in Neutrino can translate these filenames to UTF-8 representations, but you need to tell the filesystem which codepage to use via a command-line option. For more information see fs-dos.so in the Utilities Reference.

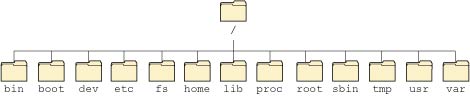

The default Neutrino filesystem generally follows the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard, but we don't claim to be compliant or compatible with it. This standard describes where files and directories should or must be placed in UNIX-style operating systems. For more information, see http://www.pathname.com/fhs.

|

The Neutrino pathname space is extremely flexible. Your system may be configured differently. |

This section describes the contents of these directories:

Click a directory to go to its description.

The / directory is the root of the pathname space. Usually your primary hard disk or flash filesystem is mounted here. On a QNX 4 filesystem, this directory includes the following files:

You must preserve the integrity of this file to prevent disk corruption. After an unexpected shutdown, run chkfsys to walk through the entire filesystem and validate this file's contents, correcting them if necessary. For more information, see "QNX 4 filesystem" in Working with Filesystems, and chkfsys in the Utilities Reference.

The / directory also contains platform-specific directories (e.g. mipsle, ppcbe, x86), as well as the directories described in the sections that follow.

The /bin directory contains binaries of essential utilities, such as chmod, ls, and ksh.

To display basic utility syntax, type use utilityname from the command line. For more information, see use in the Utilities Reference.

The /boot directory contains files and directories related to creating bootable OS images (image filesystems). Image filesystems contain OS components, your executables, and data files that need to be present and running immediately upon bootup. For general information on this topic, see Making an OS Image in the Building Embedded Systems guide, and mkifs in the Utilities Reference.

This directory includes:

As described earlier, the /dev directory belongs to the process manager. This directory contains device files, possibly including:

The actual result, therefore, varies from board to board. On a standard PC (using startup-BIOS), the default is to write to the PC console. For more information, see startup-* in the Utilities Reference.

The /etc directory contains host-specific system files and programs used for administration and configuration, including:

The default /etc/profile displays this file only if the /etc/motd file is more recent than the time you last logged in to the system, as determined by the time your $HOME/.lastlogin file was last modified. For more information, see the description of /etc/profile in Configuring Your Environment.

For more information, see Using the Photon microGUI.

For more information, see the Controlling How Neutrino Starts chapter.

Additional filesystems are mounted under /fs. See Working with Filesystems in this guide, and devb-* and mount in the Utilities Reference. This directory can include:

The home directories of regular users are found here. The name of your home directory is often the same as your user name.

A directory that contains essential shared libraries that programs need in order to run (filename.so), as well as static libraries used during development. See also /usr/lib and /usr/local/lib.

The /lib directory includes:

Owned by the process manager (procnto), this virtual directory can give you information about processes and pathname-space configuration.

The /proc directory contains a subdirectory for each process; the process ID is used as the name of the directory. These directories each contain an entry (as) that defines the process's address space. Various utilities use this entry to get information about a process.

The /proc directory also includes:

|

If you list the contents of the /proc directory, /proc/mount doesn't show up, but you can list the contents of /proc/mount. |

The /root directory is the home directory for the root user.

This directory contains essential system binaries, including:

Many of these files are used when you boot the system; for more information, see Controlling How Neutrino Starts.

This directory contains temporary files. Programs are supposed to remove their temporary files after using them, but sometimes they don't, either due to poor coding or abnormal termination. You can periodically clean out extraneous temporary files when your system is idle.

The /usr directory is a secondary file hierarchy that contains shareable, read-only data, and includes:

The /var directory contains variable data files, including cache files, lock files, log files, and the following:

Each file and directory belongs to a specific user ID and group ID, and has a set of permissions (also referred to as modes) associated with it. You can use these utilities to control ownership and permissions:

| To: | Use: |

|---|---|

| Specify the permissions for a file or directory | chmod |

| Change the owner (and optionally the group) for a file or directory | chown |

| Change the group for a file or directory | chgrp |

For details, see the Utilities Reference.

|

You can change the permissions and ownership for a file or directory only if you're its owner or you're logged in as root. If you want to change both the permissions and the ownership, change the permissions first. Once you've assigned the ownership to another user, you can't change the permissions. |

Permissions are divided into these categories:

Each set of permissions includes:

For example, if you list your home directory (using ls -al), you might get output like this:

total 94286 drwxr-xr-x 18 barney techies 6144 Sep 26 06:37 ./ drwxrwxr-x 3 root root 2048 Jul 15 07:09 ../ drwx------ 2 barney techies 4096 Jul 04 11:17 .AbiSuite/ -rw-rw-r-- 1 barney techies 185 Oct 27 2000 .Sig -rw------- 1 barney techies 34 Jul 05 2002 .cvspass drwxr-xr-x 2 barney techies 2048 Feb 26 2003 .ica/ -rw-rw-r-- 1 barney techies 320 Nov 11 2002 .kshrc -rw-rw-r-- 1 barney techies 0 Oct 02 11:17 .lastlogin drwxrwxr-x 3 barney techies 2048 Oct 17 2002 .mozilla/ drwxrwxr-x 11 barney techies 2048 Sep 08 09:08 .ph/ -rw-r--r-- 1 barney techies 254 Nov 11 2002 .profile drwxrwxr-x 2 barney techies 4096 Jul 04 09:06 .ws/ -rw-rw-r-- 1 barney techies 3585 Dec 05 2002 123.html

The first column is the set of permissions. A leading d indicates that the item is a directory; see "Types of files," earlier in this chapter.

You can also use octal numbers to indicate the modes; see chmod in the Utilities Reference.

Some programs, such as passwd, need to run as a specific user in order to work properly:

$ which -l passwd -rwsrwxr-x 1 root root 21544 Mar 30 23:34 /usr/bin/passwd

Notice that the third character in the owner's permissions is s. This indicates a setuid ("set user ID") command; when you run passwd, the program runs as the owner of the file (i.e. root). An S means that the setuid bit is set for the file, but the execute bit isn't set.

You might also find some setgid ("set group ID") commands, which run with the same group ID as the owner of the file, but not with the owner's user ID. If setgid is set on a directory, files created in the directory have the directory's group ID, not that of the file's creator. This scheme is commonly used for spool areas, such as /usr/spool/mail, which is setgid and owned by the mail group, so that programs running as the mail group can update things there, but the files still belong to their normal owners.

|

If you change the ownership of a setuid command, the setuid bit is cleared, unless you're logged in as root. Similarly, if you change the group of a setgid command, the setgid bit is cleared, unless you're root. |

|

Setuid and setgid commands can cause a security problem. If you create any, make sure that only the owner can write them, and that a malicious user can't hijack them -- especially if root owns them. |

The sticky bit is an access permission that affects the handling of executable files and directories:

If the third character in a set of permissions is t (e.g. r-t), the sticky bit and execute permission are both set; T indicates that only the sticky bit is set.

Use the umask command to specify the mask for setting the permissions on new files. The default mask is 002, so any new files give read and write permission to the user (i.e. the owner of the file) and the rest of the user's group, and read permission to other users. If you want to remove read and write permissions from the other users, add this command to your .profile:

umask 006

If you're the system administrator, and you want this change to apply to everyone, change the umask setting in /etc/profile. For more information about profiles, see Configuring Your Environment.

This table lists some common filename extensions used in a Neutrino system:

| Extension | Description | Related programs/utilities |

|---|---|---|

| .1 | Troff-style text, e.g. from UNIX "man" (manual) pages. | man and troff in the third-party repository |

| .a | Library archive | ar |

| .awk | Awk script | awk |

| .b | Bench calculator library or program | bc |

| .bat | MS-DOS batch file | For use on DOS systems; won't run under Neutrino. See Writing Shell Scripts and ksh for information on writing shell scripts for Neutrino. |

| .bmp | Bitmap graphical image | pv (Photon viewer) |

| .build | OS image buildfile | mkifs |

| .c | C program source code | qcc, make (QNX Momentics development system required) |

| .C, .cc, .cpp | C++ program source code | QCC, make (QNX Momentics development system required) |

| .cfg | Configuration files, various formats | Various programs; formats differ |

| .conf | Configuration files, various formats | Various program; formats differ |

| .css | Cascading style sheet | Used in the QNX Momentics PE development system for Eclipse documentation |

| .def | C++ definition file | QCC, make (QNX Momentics development system required) |

| .dll | MS-Windows dynamic link library | Not used directly in Neutrino; necessary in support of some programs that run under MS-Windows, such as some of the QNX Momentics development tools. See .so (shared objects) for the Neutrino equivalent. |

| .gif | GIF graphical image | pv (Photon viewer) |

| .gz | Compressed file | gzip; Backing Up and Recovering Data |

| .h | C header file | qcc, make (QNX Momentics development system required) |

| .htm | HyperText Markup Language (HTML) file for Web viewing | voyager web browser |

| .html | HyperText Markup Language (HTML) file for Web viewing | helpviewer, voyager web browser |

| .ifs, .img | A QNX Image filesystem, typically a bootable image | mkifs; see also Making an OS Image in Building Embedded Systems (QNX Momentics development system) |

| .jar | Java archive, consisting of multiple java files (class files etc.) compressed into a single file | Java applications e.g. the QNX Momentics PE IDE |

| .jpg | JPEG graphical image | pv (Photon viewer) |

| .kbd | Compiled Photon keyboard definition files | Photon, mkkbd |

| .kdef | Source Photon keyboard definition files | mkkbd |

| .mk | Makefile source, typically used within QNX recursive makes | make (QNX Momentics development system) |

| .o | Binary output file that results from compiling a C, C++, or Assembly source file | qcc, make (QNX Momentics development system) |

| .pal | Photon palette file | Photon |

| .pfr | Bitstream TrueDoc Portable Font Resource file | phfont |

| .phf | Bitmapped font file | phfont |

| .qpr | Neutrino installation package repository; a gzipped tar archive of .qpm, .qpk, and .qrm files | qnxinstall, cl-installer |

| .qpm | Neutrino package manifest | Usually found in a package repository (.qpr); qnxinstall, cl-installer |

| .qpk | Neutrino package contents | Usually found in a package repository (.qpr); qnxinstall, cl-installer |

| .qrm | Neutrino package repository manifest | Usually found in a package repository (.qpr); qnxinstall, cl-installer |

| .S, .s | Assembly source code file | GNU assembler as (QNX Momentics development system) |

| .so, .so.n | Shared object | qcc, make (QNX Momentics development system) |

| .tar | Tape archive | tar; Backing Up and Recovering Data |

| .tar.gz, .tgz | Compressed tape archive | gzip, tar; Backing Up and Recovering Data |

| .toc | Helpviewer table of contents file | helpviewer |

| .TTF | TrueType fonts | phfont |

| .txt | ASCII text file | Many text-based editors, applications, and individual users |

| .ttf | TrueType font file | phfont |

| .use | Usage message source for programs that don't embed usage in the program source code (QNX recursive make) | make (QNX Momentics development suite) |

| .wav | Audio wave file | phplay |

| .xml | Extensible Markup Language file; multiple uses, including IDE documentation in a QNX Momentics PE development system | |

| .zip | Compressed archive file | gzip |

If you aren't sure about the format of a file, use the file utility:

file filename

Here are a few problems that you might have with files:

![[Previous]](prev.gif) |

![[Contents]](contents.gif) |

![[Index]](keyword_index.gif) |

![[Next]](next.gif) |