![[Previous]](prev.gif) |

![[Contents]](contents.gif) |

![[Index]](keyword_index.gif) |

![[Next]](next.gif) |

![[Previous]](prev.gif) |

![[Contents]](contents.gif) |

![[Index]](keyword_index.gif) |

![[Next]](next.gif) |

This chapter includes:

This section describes how the QNX Neutrino RTOS compares to UNIX and Microsoft Windows, from a user's (not a developer's) perspective. For more details about Neutrino's design and the philosophy behind it, see the System Architecture guide.

If you're familiar with UNIX-style operating systems, you'll feel right at home with QNX Neutrino -- many people even pronounce "QNX" to rhyme with "UNIX" (some spell it out: Q-N-X). At the heart of the system is the Neutrino microkernel, surrounded by other processes and the familiar Korn shell, ksh (see the Using the Command Line chapter). Each process has its own process ID, or pid, and contains one or more threads.

Neutrino is a multiuser OS; it supports any number of users at a time. The users are organized into groups that share similar permissions on files and directories. For more information, see Managing User Accounts.

Neutrino follows various industry standards, including POSIX (shell and utilities) and TCP/IP. This can make porting existing code and scripts to Neutrino easier.

Neutrino's command line looks just like the UNIX one; Neutrino supports many familiar utilities (grep, find, ls, awk) and you can connect them with pipes, redirect the input and output, examine return codes, and so on. Many utilities are the same in UNIX and Neutrino, but some have a different name or syntax in Neutrino:

| UNIX | Neutrino | See also: |

|---|---|---|

| adduser | passwd | Managing User Accounts |

| at | cron | |

| fsck | chkfsys, chkdosfs | Backing Up and Recovering Data |

| ifconfig eth0 | ifconfig en0 | TCP/IP Networking |

| lp | lpr | Printing |

| lpc | lprc | Printing |

| lpq, lpstat | lprq | Printing |

| lprm, cancel | lprrm | Printing |

| man | use | Using the Command Line |

| pg | less, more | Using the Command Line |

For details on each command, see the Neutrino Utilities Reference.

QNX Neutrino and Windows have different architectures, but the main difference between them from a user's perspective is how you invoke programs. Much of what you do via a GUI in Windows you do in Neutrino through command-line utilities, configuration files, and scripts, although Neutrino does support a powerful Integrated Development Environment (IDE) to help you create, test, and debug software and embedded systems.

Here are some other differences:

textto -l my_file

To convert the end-of-line characters to DOS-style:

textto -c my_file

Although Neutrino is powerful enough to use as a desktop OS, we don't provide desktop applications such as word processing, spreadsheets, or email. Some of these applications might be available from other sources, such as the third-party repository.

If you're using Neutrino to support self-hosted QNX Momentics development, you'll likely require an email solution of some sort. We suggest you consider using an email client or Mail User Agent such as Mozilla, mutt, or elm, along with the sendmail delivery agent; see the third-party repository.

You might find it useful to run an IMAP or POP server on another machine to host your email if you don't want to configure a local mail delivery using sendmail. Or, you may avoid using a local email client entirely by using a web-based mail service hosted on another machine.

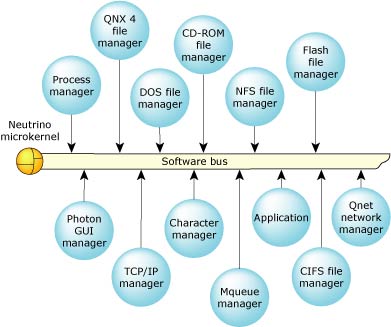

Neutrino consists of a microkernel and various processes. Each process -- even a device driver -- runs in its own virtual memory space.

The QNX Neutrino architecture.

The advantage of using virtual memory is that one process can't corrupt another process's memory space. For more information, see The Philosophy of QNX Neutrino in the System Architecture guide.

Neutrino's most important features are its microkernel architecture and the resource manager framework that takes advantage of it (for a brief introduction, see "Resource managers," below). Drivers have exactly the same status as other user applications, so you debug them using the same high-level, source-aware, breakpointing IDE that you'd use for user applications. This also means that:

Developers can usually eliminate interrupt handlers (typically the most tricky code of all) by moving the hardware manipulation code up to the application thread level -- with all the debugging advantages and freedom from restrictions that that implies. This gives Neutrino an enormous advantage over monolithic systems.

Likewise, in installations in the field, the modularity of Neutrino's components allows for the kind of redundant coverage expressed in our simple, yet very effective, High Availability (HA) manager, making it much easier to construct extremely robust designs than is possible with a more fused approach. People seem naturally attracted to the ease with which functioning devices can be planted in the POSIX pathname space as well.

Developers, system administrators, and users also appreciate Neutrino's adherence to POSIX, the realtime responsiveness that comes from our devotion to short nonpreemptible code paths, and the general robustness of our microkernel.

Neutrino's microkernel architecture lets developers scale the code down to fit in a very constrained embedded system, but Neutrino is powerful enough to use as a desktop OS. Neutrino runs on multiple platforms, including x86, ARM, MIPS, PPC, and SH-4, and it supports symmetric multiprocessing (SMP).

Neutrino also features the Qnet protocol, which provides transparent distributed processing -- you can access the files or processes on any machine on your network as if they were on your own machine.

A resource manager is a server program that accepts messages from other programs and, optionally, communicates with hardware. All of the Neutrino device drivers and filesystems are implemented as resource managers.

Neutrino resource managers are responsible for presenting an interface to various types of devices. This may involve managing actual hardware devices (such as serial ports, parallel ports, network cards, and disk drives) or virtual devices (such as /dev/null, the network filesystem, and pseudo-ttys).

The binding between the resource manager and the client programs that use the associated resource is done through a flexible mechanism called pathname-space mapping. In pathname-space mapping, an association is made between a pathname and a resource manager. The resource manager sets up this mapping by informing the Neutrino process manager that it's responsible for handling requests at (or below, in the case of filesystems), a certain mountpoint. This allows the process manager to associate services (i.e. functions provided by resource managers) with pathnames.

Once the resource manager has established its pathname prefix, it receives messages whenever any client program tries to do an open(), read(), write(), etc. on that pathname.

For more detailed information on the resource manager concept, see Resource Managers in System Architecture.

![[Previous]](prev.gif) |

![[Contents]](contents.gif) |

![[Index]](keyword_index.gif) |

![[Next]](next.gif) |